Portadown's development continued to be modest during the eighteenth century. As an urban centre it was eclipsed by the ecclesiastical city of Armagh and the bustling market town of Lurgan. The latter was the chief marketing centre for linen production in the area. Quaker merchants from Lurgan and Moyallon purchased webs of unbleached cloth from the local handloom weavers and carried out the bleaching process before selling on the finished product in Dublin or England. The town of Portadown remained somewhat of a backwater with landlords who did much less to foster trade and encourage commerce than did their Brownlow counterparts in Lurgan. In Quaker terms the focus of activity continued to be based in Lurgan, Moyallon or Ballyhagan (later Richhill).

Mary Dudley, an English Friend who came to live in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, records in a Journal her travels in the ministry in 1795 when she visited many of the Ulster meetings. On March 8 she attended Sunday morning meeting in Lurgan and she states that in the afternoon she

"set forward to Portadown, a place where no Friends reside, and found a great number of people waiting about the door of a large room at an inn, which had been previously seated; and was soon much crowded, many standing without: yet there was a remarkable quietness, and more liberty in proclaiming the gospel than is usually felt in this day among members of our own Society."

For the good citizens of Portadown the experience of a woman preacher must have enlivened their quiet Sunday afternoon.

The opening of the Newry Canal in 1741 and the Lagan Canal in 1763 was of immense importance to Portadown for they offered valuable links to the ports of Newry and Belfast. Markets for both linen and agricultural products were soon set up in the town. Unlike Lurgan, however, Friends had little part in this commercial development. Most of the pioneers of Portadown's mercantile life at this period came from the newly emergent Methodist movement. Families such as Shillington, Paul, Cowdy, Robb, Lutton and Thornton contributed much to the business and religious life of the district.

John Wesley on his first visit to the town in 1767 spoke of Portadown as 'a place not troubled with any kind of religion'.

However he was to find a ready response to his preaching among the people of the area. Jack Gilpin points out in his History of Ballinacor Methodist Society that many of the original members came from a Quaker background.

Until 1802 there was no place of worship in the town, when a Methodist chapel was opened on a site near Church Lane, off West Street. The Portadown district remains to the present day one of the strongest centres of Methodism in Ireland, with three churches in the town and a further four within a three-mile radius.

As the nineteenth century advanced so the town of Portadown progressed and grew in confidence. In 1820 the last surviving member of the Obins family transferred his property to his kinsfolk, the Sparrows of Tandragee. In 1822 his cousin, Millicent Sparrow, married Lord Mandeville, later sixth Duke of Manchester. Both the Duke and Duchess took a warm interest in Portadown and did much to foster its development. The Duke was a staunch Churchman and granted the prominent site of St. Mark's Church, as well as donating a generous sum towards the cost of its building. The first Presbyterian Church was established in 1822 in Edenderry and the Roman Catholic Church in William Street was built in 1835. A new Methodist Church was also erected in 1832, to be replaced by the present Church in Thomas Street in 1860.

The population of the town grew rapidly in the course of the 1800s. In 1814 there were 767 inhabitants. By 1831 the population had more than doubled and by the end of the century it exceeded 10,000. The growth of the town was stimulated by arrival of the railway link to Belfast in 1842, and by the industrialisation of the linen industry in the latter half of the century. New spinning, weaving and hemstitching factories were set up which made the production of linen as a cottage industry almost redundant. New housing convenient to the linen factories attracted workers from the countryside into the town.

Other events in the middle part of the century caused great social disruption and distress. In the middle to late 1840s the Great Irish Famine was a time of immense suffering in the area. Armagh was at that time the most densely populated county in Ireland. It was possible to make a living from a smallholding of four or five acres and the proceeds of handloom weaving but life was precarious in times of economic stress or crop failure. Lists of admissions to Lurgan Workhouse and records of deaths which occurred there provide eloquent witness to the hard times experienced by many.

Friends in Ireland took action to alleviate distress in all parts of the country. Thomas C. Wakefield of Moyallon was a corresponding member of the Central Relief Committee, as were other Friends in Moy, Lisburn and Dungannon. In the carefully documented records of Friends Transactions we read of substantial amounts of food being allocated for distribution in Portadown as follows:

| 28 April 1847 | James Saurin (Rector of Seagoe) | 1 ton Indian meal |

| 28 April 1847 | Simon Foot (Rector of Knocknamuckley) | 1 ton rice |

| 15 May 1847 | Charles Wakefield, Portadown | 1/2 ton East Indian rice, 2 tons Carolina rice, 28 lb ginger |

| 19 June 1847 | Charles Babbington (Rector of Drumcree) | 1 ton rice, 1 boiler |

| 23 June 1847 | Henry Willis (Perpetual Curate of Portadown) | 1 ton rice |

In addition clothing was made available for the most needy and distributed as set out below:

| 12 December 1848 | Elizabeth Wakefield, Moyallon | 1 pair corduroy, 1 pair fustian, 1 pair flannel, 1 pair calico, 12 rugs, 6 pairs sheets, 3 grey frocks, 60 garments, 5 coats, 2 quilts, 12 waistcoats, 2 blankets, 1 gown, 10 chemises. |

| No Date | Anne Wakefield & Ann Babbington, Portadown | 6 coats, 6 pairs mens' trousers, 4 mens' vests, 4 boys' vests, 2 worsted dresses, 6 bedgowns, 3 boys' capes, 18 children's dresses, 24 girls' & women's chemises, 52 pairs sheets, 4 cloaks, 12 shirts, 30 children's coats, 2 pairs flannel, 6 woollen capes,7 boys' capes, 2 guernsey frocks, 2 boys' jackets, 2 pairs gaiters, 2 girls' coats, 50 girls & women's petticoats, 2 men's smocks, 2 men's capes, 2 pairs men's trousers. |

Money grants were also made for general distress and for specific purposes. One scheme was for the distribution of carrot, parsnip and especially turnip seed to improve the nutritional diet of the people. Another was to provide nets and tackle for fishing on Lough Neagh. One of the local agents for the Quaker relief organisation was John Dilworth who lived in the townland of Bocombra, about two miles on the Lurgan side of Portadown. He was so distressed by the magnitude of the suffering which he witnessed in the area that he wrote to the Belfast Newsletter in the following harrowing terms:

"Employed in administering the benevolence of Christian friends in England, I have met with some most deplorable cases which, I think, cannot be exceeded even in the south of Ireland. About the beginning of this month, in the course of my visitings, I called on a family named McClean - found the house like a pig-sty - having fled from the Lurgan poor-house, where fever and dysentry prevailed - they returned home, only to encounter greater horrors. Want sent the poor man to bed. I gave him some assistance, but he died a few days later. The wife, almost immediately after, met the same melancholy fate; and a daughter soon followed her parents to the grave. I found all the members of the family very ill, except one boy, who, with the help of others, put the deceased into their coffins. On the Thursday after, I repeated my visit; and, just within the door of the wretched habitation, I saw a young man, about twenty years old, sitting before a live coal, about the size of an egg, entirely naked; and another lad, about thirteen, leaning against a post. On turning to the right, I saw a quantity of straw, which had become litter; the rest of the family, reclining on this wretched bed, also naked, with an old rug for covering....My attention was directed to an object at my feet, and over which I nearly stumbled, the place being so dark - and, oh! what a spectacle! a young man about fourteen or fifteen, on the cold damp floor - dead! - without a single vestige of clothing - the eyes sunk - the mouth wide open - the flesh shrivelled up - the bones all visible - so small around the waist, that I could span him with my hand. I was greatly shocked, and got as much money as purchased a coffin, had the remains interred, produced several articles of nourishment for the survivors, and the next day brought various garments suited to their necessities."

John Dilworth returned the following week and found another of this family dead. His letter concludes:

"Out of eight members of a family, three only now survive; and I understand that the doctor who has visited them through the past week, states that none of these will be any time alive. This famine is stalking through our land, and pestilence, in her train, is accomplishing the work of destruction. How necessary to humble ourselves before the Lord, and to implore his mercy. I remain, Sir, your most humble servant.

John Dilworth, O'Neiland Cottage, Portadown 27th March, 1847."

The religious revival of 1859 had a profound influence on the North of Ireland and its effects were very evident in the Portadown area. Open Air meetings held in fields on the banks of the Bann attracted large crowds and many people came to a new experience of faith. A report on conditions in Ireland for the benefit of immigrants, published in Philadelphia in 1860, tells of how Orange Lodges voluntarily abandoned their traditional Twelfth of July parades and how Orangemen and Roman Catholics were seen peacefully conversing and exchanging expressions of kindness.

The Quaker journal The Friend' has a report of a visit in the ministry by William Tanner of Bristol and his mother, Mary, in October 1859. They were overwhelmed by the enthusiastic reception they received not only from Friends but from the general populace. They visited most of the meetings in Ulster and also had invitations to speak in Presbyterian and Baptist churches in Coleraine, Ballymena and near Dungannon. They report that about 500 were present at the meeting in Lurgan and some hundreds went away, unable to gain admission to the meeting house. In Portadown a public meeting was arranged in the Town Hall (at that time on the site of the Halifax pic premises on the corner of Woodhouse St. and High St.).

Again they report that it was 'much crowded, hundreds going away for want of room'.

Surely a rare occurence for Friends Meetings! The report on their time in Ulster concludes with the comment:

'Much openness was manifested in the minds of the people towards our Friends, and many expressed their satisfaction that such meetings had been held. The demand for Friends' tracts in some districts of the north of Ireland during the last four months, has been beyond all precedent, and upwards of 40,000 have been lately put into circulation.'

The effect of this revival movement was felt in Quaker circles in Ulster for many decades. New interest was stirred in mission work at home and abroad, ministry in meetings became more vigorous and admissions to membership were noted in many places. These factors were soon to impact on the growing town of Portadown.

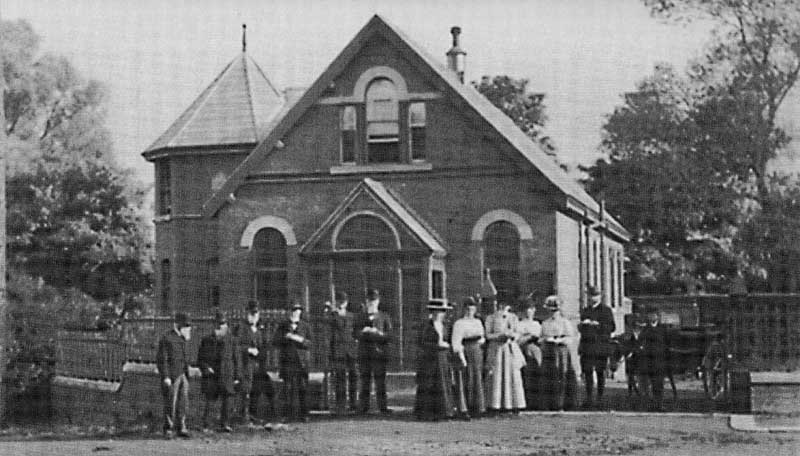

Mary Lamb (Richhill), Kathleen Lamb (Richhill), Mary Green, nee Shemeld (Antrim) Henrietta Bulla (Lisburn), Alice Bulla (Belfast),

C. Walpole Marsh (Belfgast), E. Forster Green, grandson of Albert Shemeld.

The picture was taken by the celebrated photographer, W. A. Green, son-in-law of Albert Shemeld

If you would like to contribute then please click on the Donate button.

Thank you for your support.